A sitting deputy prime minister has stepped down over a property tax error. That alone tells you how fragile trust is in British politics right now.

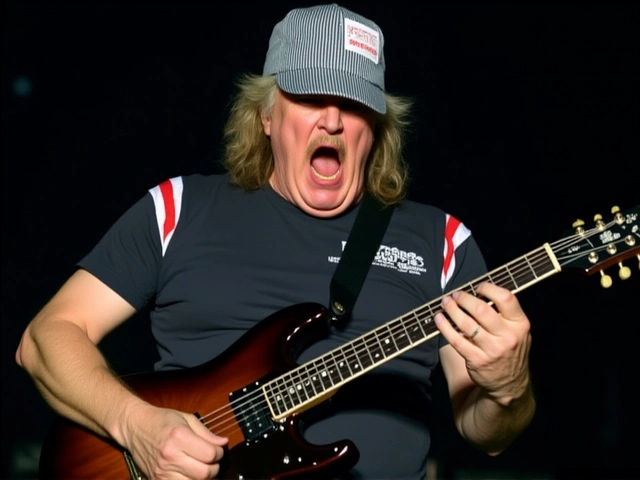

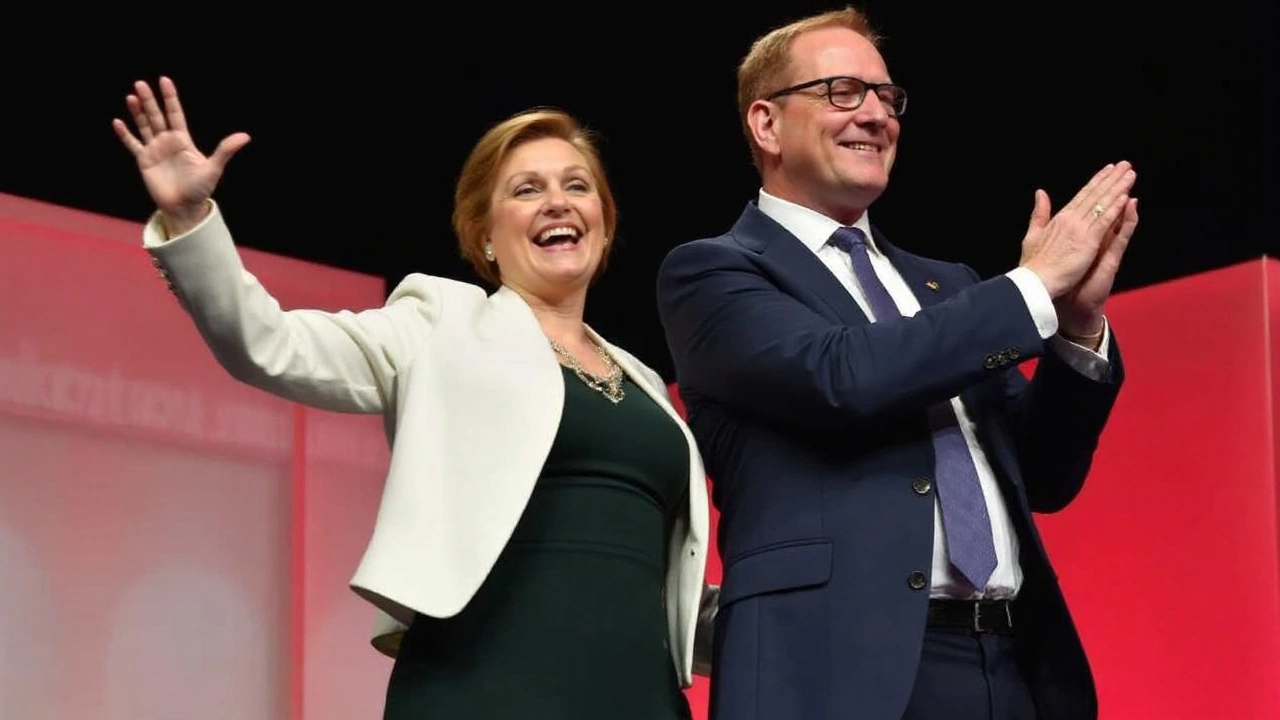

Angela Rayner resigned as deputy prime minister and housing secretary on Friday, 5 September 2025, after admitting she underpaid stamp duty on an £800,000 seaside flat in Hove. She referred herself to the government’s ethics watchdog, accepted she breached the ministerial code, and left office the same day. Keir Starmer, who had publicly backed her through weeks of pressure, has now begun a fast reshuffle, naming Foreign Secretary David Lammy as the new deputy prime minister.

The decision ends a bruising episode for a senior figure who helped drive Labour’s election machine and shaped its housing pitch. It also puts a spotlight on the tangle of tax rules around second homes, trusts, and what counts as someone’s main residence — and on how high the bar is for ministers when those rules get muddled.

What triggered the resignation

The chain of events began with Rayner’s purchase of an £800,000 flat in Hove. Because she already had a stake connected to a family home, the transaction fell into the “additional property” bracket. That triggers higher stamp duty charges than a standard main home purchase. Her bill should have reflected those higher rates. It didn’t.

Rayner said she relied on professional advice and later learned parts of it were wrong. She told the prime minister she regretted not seeking deeper specialist guidance before completion. The Independent Adviser on Ministers’ Interests, Sir Laurie Magnus, reviewed the case. His finding was blunt and nuanced at the same time: he said Rayner acted in good faith and showed integrity, yet failed to heed clear caution in the legal advice she did receive. The upshot — a technical breach that still counts as a breach.

The personal backdrop made the situation messier. After divorcing in 2023, Rayner and her ex-husband, Mark Rayner, set up a “nesting” arrangement so their son could stay full-time in the family house while the parents rotated in and out. Part of the property was placed into a trust, with both parents and a law firm, Shoosmiths, acting as trustees. Rayner then sold her remaining stake in the Ashton house to the trust in January, with her name removed from the deeds. That structure, and the question of where she was truly “based” for tax purposes, layered complexity onto the Hove purchase.

That complexity matters. Stamp duty rules treat a “main residence” differently from an “additional dwelling.” When trusts and partial interests are involved, HMRC looks at beneficial ownership, not just whose name sits on the deeds. If you end up classed as buying an extra property, higher rates apply and thresholds shift. That’s where Rayner’s case ran into trouble.

Rayner accepted the breach in her resignation letter, while pointing to the unusual nature of the arrangement and the needs of her disabled son as material context. She said she took responsibility for the error and acknowledged she fell short of the standards she expects of herself and others in public office.

Public reaction split quickly. Some voters and commentators praised the choice to resign as an act of accountability that has become rare in Westminster. Others called it overdue and said the episode undercut Labour’s promise to govern with clean hands. Many expressed sympathy for the family circumstances and the trust arrangements, but still felt the bar for ministers is unforgiving — and has to be.

Starmer, who had spent days swatting away accusations that his deputy was a “tax evader,” said he respected the adviser’s judgment and Rayner’s decision. He moved to steady the ship with a reshuffle that puts David Lammy in the deputy PM slot. The switch consolidates power with a close ally and signals the government wants to keep foreign, economic, and domestic policy aligned under a small inner circle while the storm passes.

The ethics ruling, the tax rules, and the fallout

This is not the first time a minister has been tripped up by the ministerial code. But the contours are familiar: a complex personal or financial issue, a dispute about advice, and a clear expectation that ministers must solve the complexity before signing on the dotted line. The code demands honesty and leadership by example. When the independent adviser finds a breach — even without bad intent — resignation is often the cleanest route back to credibility for the government.

Sir Laurie Magnus’s role is advisory. He doesn’t sack ministers. He investigates, writes up the facts, and offers a view on whether the code is breached. The prime minister decides the sanction. This time, the adviser’s judgment that Rayner acted with integrity but failed to meet the highest standard gave Starmer cover to accept her resignation rather than fight on. It also set a marker: good faith is not a shield when the rules are crystal clear and warnings are on paper.

So what, exactly, went wrong with the tax? Stamp duty ramps up sharply on additional properties. Even when a buyer plans to live in the new place, HMRC tests whether the old one was truly sold or ceased to be their main home, and whether any interests remain. Trusts add another layer: if you benefit from a trust that holds property, tax law may still treat you as having an interest in a dwelling. It’s a technical maze built to stop people dodging higher rates, and it catches genuine mistakes too.

That’s why lawyers usually tell buyers with complicated family setups to get specialist advice before exchange. The adviser’s report suggests Rayner had some warnings but pressed ahead without fully reconciling them. That decision — not the family context itself — is what triggered the breach.

There’s also the question of money owed. HMRC can charge the underpaid amount, add interest, and impose a penalty depending on the degree of care taken. None of those details were made public on Friday, and any settlement would be between Rayner and the tax authority. Still, the political cost has already landed: the loss of the deputy prime minister and housing brief at a time when the government wants to show grip on the cost of living and the housing shortage.

For Labour, the timing is rough. The housing secretary’s agenda was full: planning reform, build-out rules for stalled sites, renter protections, and nudging local authorities to get more homes approved without watering down environmental and design standards. Even straightforward policies take months to draft and pass; anything controversial can drag for a year. A change of minister adds delay — and invites lobby groups to rerun arguments they thought they’d lost.

David Lammy stepping up as deputy prime minister is the headline, but the real test is the next round of appointments beneath him. Who takes the housing portfolio? Do they keep the same priorities? Do they change tone with developers, councils, and renters? People watch for signals in the first week — what the new minister says about planning backlogs, brownfield funding, and local targets tells you whether the strategy stays intact.

Opposition parties are already framing the resignation as proof that Labour is no different from past governments when it comes to standards. Expect them to ask why the issue wasn’t settled before the purchase and whether other ministers have undisclosed tax or property entanglements. That broader push on probity won’t stop here. Ethics rows are contagious in Westminster; once the spotlight turns to disclosures and forms, more questions usually follow.

Inside Labour, the focus is survival and continuity. Rayner was not just a deputy in title; she was a political operator with union ties, a campaigner who connected with parts of the country Labour needs to keep, and a voice on social policy that balanced the party’s technocratic streak. Replacing that mix won’t be simple. The party will want her back on the front line after a period out of government, even if only on the backbenches for now. Whether she chooses that path depends on how the next few weeks unfold.

One thing to watch: how quickly the government can close the file. If HMRC issues a final tax calculation and any penalty, getting that resolved fast would shrink the story and remove guesswork. Delays breed suspicion. The same goes for transparency: when ministers publish clear timelines of what they knew and when, controversies fade sooner. When they don’t, they linger.

The family trust angle will keep lawyers debating. Trusts aren’t exotic anymore — many families use them to protect vulnerable beneficiaries, manage inheritance, or handle complicated living arrangements after divorce. But when a trust holds property, the lines between legal title and beneficial interest often blur for tax. People assume that if their name is off the deeds, the taxman sees it the same way. Not always. And for public officials, assuming is risky.

For voters, the core question is simpler: can the people in charge follow their own rules? Ministers set tax policy and enforce compliance on everyone else. If they fall short, they have to show that the system treats them no better than anyone else. That’s why resignations over even technical breaches carry weight. They’re a message: the rules apply at the top, too.

There’s also the practical side of running the country. Reshuffles are distractions. They eat time, create uncertainty, and slow decisions. Civil servants wait to see what the new minister wants. Stakeholders resend their briefings. Journalists look for rifts. A government that came in promising stability will want to move past this quickly and get back to the business of building homes, easing rents, and unblocking stalled planning cases.

Key moments in the saga so far:

- Rayner buys an £800,000 flat in Hove, later found to be treated as an additional property for stamp duty.

- She refers herself to the ethics watchdog as questions mount about underpaid tax.

- Independent Adviser Sir Laurie Magnus finds she acted with integrity but failed to meet the code’s highest bar, citing ignored caution in legal advice.

- Rayner resigns as deputy prime minister and housing secretary on 5 September 2025.

- Keir Starmer launches a reshuffle and appoints David Lammy as deputy prime minister.

What we don’t know yet matters, too. We don’t know the exact amount of underpaid tax, interest, or any penalty. We don’t know whether Rayner will take a break from front-line politics or stay highly visible on the backbenches. We don’t know who will lock down the housing brief and how that person will handle pressure from developers, renters, and councils. Those answers will shape the next phase.

For now, the political lesson is straightforward. Ministers don’t get to be casual about complicated personal finances, especially when property is involved. The public doesn’t care if the rulebook is dense. They expect the people who write it to follow it — and to step aside if they don’t.

Rayner’s departure hurts the government in the short term. But the way it was handled — a quick investigation, an acceptance of fault, and a clean exit — may limit the damage. The faster the next housing secretary sets a clear plan, the sooner the focus will shift from a tax bill in Hove to whether Labour can actually build the homes it promised.

In the end, it was a judgment call — not about who Angela Rayner is, but about what a minister must do when personal complexity collides with public duty. She chose to go. Now the government has to show that the policies she championed will outlast the person who carried them.